Creating sustainable public health solutions in Tanzania

By Julia Sherry (MS/MPH '17)

In an introductory level class on natural resources my freshman year of college, I heard a lecture on the global water crisis and learned that almost a billion people lack access to safe drinking water. I couldn’t sleep that night, imagining how hard a life without safe water would be, and lay awake in my bed considering both the nightmare of people sick and dying due to preventable waterborne diseases and the dream of this problem being solved.

Five years later, I found myself in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, working as a research assistant on a project designed to provide sustainable water services to people in Tanzania. The project was funded by the World Bank and carried out by the Government of Tanzania and Water Mission, a nonprofit humanitarian organization.

Only around half of Tanzania’s population has access to an improved water source, and many people have to travel long distances, wait in long lines, or drink poor quality water on a daily basis. Even in the big city of Dar es Salaam, very few people in the communities where we worked had water piped into their home, and most had to walk to a kiosk somewhere around them to buy and carry buckets of water to their house to drink, and to use for cooking, cleaning, and bathing.

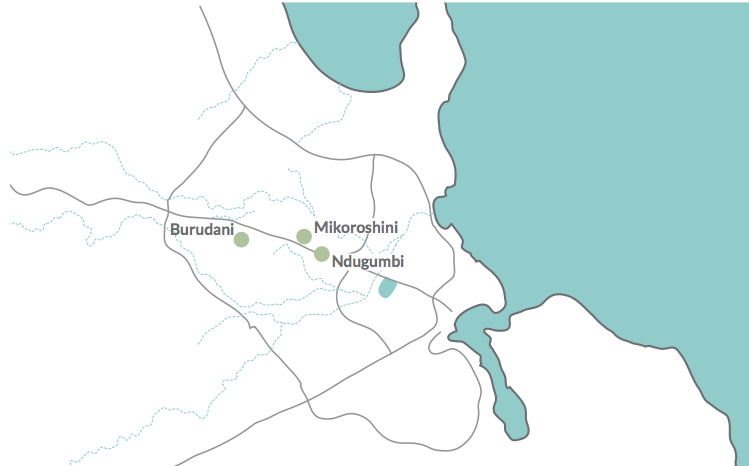

I spent the first week in Tanzania walking around the communities where we were doing research and learning about how people get their water resources. We conducted our research in a part of Dar es Salaam that is full of densely packed homes made of cinder blocks arranged in small and seemingly random alleys, where streams of water, waste, and trash cut through the neighborhood. People do not have property rights, and this settlement developed informally over time, as people headed to the city from rural areas in search of economic opportunity. Their water services are also piecemeal, with kiosks where people can come buy water, random privately owned water tanks where people vend water, and even places where people illegally tap into the public water supply and resell this water to their neighbors.

As we talked to people and asked questions about where they buy water, how much they pay, and their satisfaction with their water services, we heard multiple stories about failed water projects in the past. People recounted stories of researchers, government officials, NGO workers, and development banks coming in with promises of better quality water. Some actually built new infrastructure; however, all of these stories ended with failure. The researchers never came back and fulfilled their promises, the new infrastructure broke and was never fixed, or officials promised to pipe water into their homes for a small fee but nothing ever came.

In the past few decades, hundreds of thousands of dollars have been poured into the water supply infrastructure in Tanzania. The stories people recounted to us bring to life the unfortunate reality that investments in the Tanzanian water sector are not always successful or sustainable. A 2014 study conducted by the Ministry of Water in Tanzania revealed that of the 74,331 water points surveyed, 38 percent were nonfunctional and another 7 percent were in need of repair. I learned that a primary mission of public health work is not just to do good things, but to be thoughtful and to do good work that will last. In classes, we talk about ownership and community based participatory research — that communities themselves have knowledge that we do not have as outsiders, and that they are the best people to design and inform strategies to meet the real needs of the community. I saw this truth come to light through my work in Tanzania.

I worked alongside an amazing team of people who work for Water Mission Tanzania. Water Mission is a nonprofit Christian engineering organization that provides sustainable safe water solutions to people in developing countries and during disasters. The office was filled with hard working people who are passionate about transforming people’s lives through sustainable safe water solutions. I learned that creating partnerships with the government and other existing community resources is vital. I got to work at the office alongside many Tanzanians passionate about seeing universal access to safe water in their country. I also learned that I did not waste my time trying to learn statistics and data mapping software in class, as I got to apply those skills to real life problems.

This experience has changed the way I approach my classes this year and grounded concepts I learned in class in real life. It made me even more passionate about water and health, and even more convinced that sustainable access to safe water can transform lives.