Summer 2020 ILE projects focus on how COVID-19 has impacted safety in food distribution, first responder mental health, and small animal veterinary practices

By clicking the tabs below, you can read about each student team's Public Health Integrative Learning Experience (ILE) completed during summer 2020. Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic was at the core of each project. Student teams were able to assist their community partner during this uncertain time by producing meaningful deliverables. These deliverables have helped each partner organization respond to the pandemic and continue to serve their stakeholders and wider communities.

Sara Fleckenstein - DVM/MPH student, Infectious Disease concentration

Madalyn Fox - MPH student, Infectious Disease concentration

Grace Zhang, DVM - MPH student, Public Health Education concentration

MPH students Sara Fleckenstein, Madalyn Fox, and Grace Zhang completed their Integrative Learning Experience (ILE) with Plenty!, a nonprofit community-based food pantry and home delivery program located in Floyd, Virginia that provides education, recipes, and cooking tutorials to the local area community. Plenty!’s mission is to nourish the Floyd community by growing and sharing fresh, healthy food.

The student ILE project, Promoting Health and Safety with Plenty!, focused on addressing Plenty!’s needs for educational content and COVID-related process review, with objectives of the following:

- Evaluating the organization’s current biosecurity policies and practices and creating recommendations to improve client and staff safety as needed

- Creating culturally competent, relevant COVID-19 biosecurity and food safety content to complement existing programming in an accessible format and translated for low-literacy and Spanish-speaking audiences

- Creating culturally competent, relevant health and nutrition educational content to complement their existing programming in an accessible format.

The focus on Spanish-speaking and low-literacy populations stemmed from a patron survey that Plenty! previously conducted. Survey results indicated that many community members have low-literacy and there is a large Spanish-speaking community in the area Plenty! serves.

The team’s first deliverables were COVID-19 protocols. As COVID-19 is a novel virus, Plenty! was one of many businesses that did not yet have a comprehensive plan in place. The protocols that the student team developed were addressed to an audience of not only volunteers and staff, but also the patrons that use Plenty!’s services. The team noted that many of the formal guidelines were difficult to read due to the density of information. Additionally, recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were constantly changing, requiring them to revise their recommendations to match the frequent CDC updates.

The team ultimately developed a total of seven protocols, ranging from information for patrons, cleaning protocol documents, operational procedures, farm operations, to protocols in the event that staff or volunteers test positive for COVID-19. In addition to making seven individual protocols for each of the topics that were shown, they also developed a 17-page, in-depth document for senior management. The simplified, individual protocols could be given to staff, volunteers, and patrons, and the larger, more-detailed document was provided as a reference for management.

The flyer that Plenty! requested most urgently was one that would summarize the information provided by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and CDC. The student team condensed this information into single sheets with pictures addressing topics that seemed to be most worrying to the target audience. For example, for those concerned about how long the virus can live on the box of food that they picked up, there was a flyer showing this topic simply and concisely. All materials were provided to Plenty! in both Spanish and English and also in Word document format, so that staff could edit these easily as coronavirus information and protocols changed over time.

The next deliverable was newsletter content. The team first analyzed the audience they were addressing. A recent survey Plenty! conducted indicated that they served a variety of households that ranged from single-person households to more-than-four-people households, including children and adults older than 60. A majority of patrons reported having more than one chronic health condition, so the team wanted to be sure to address this in the newsletter content.

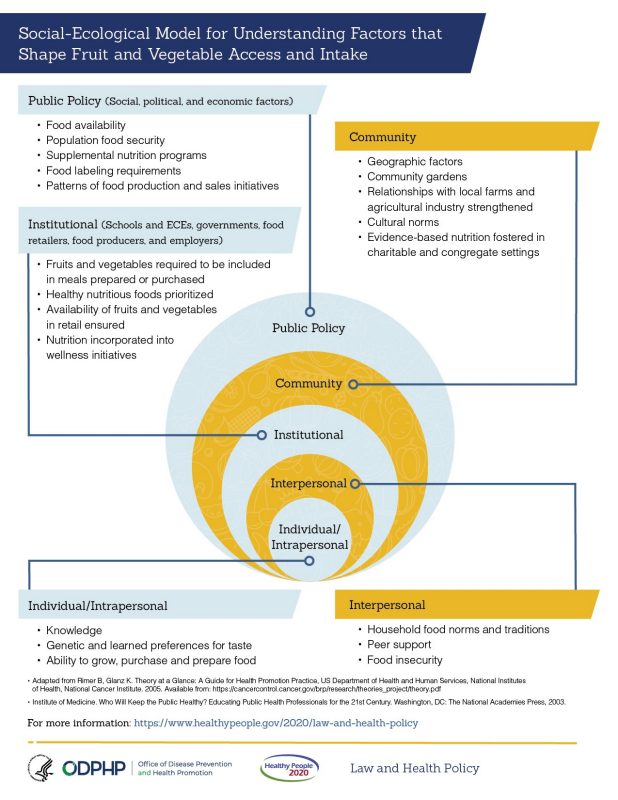

In terms of theory, the team felt that the social-ecological model and the social cognitive theory were the most appropriate. When looking at Plenty!’s work using the social ecological lens, the team found that Plenty! addressed health behavior at the levels of the community, institution, interpersonal, and individual, which creates a greater likelihood of creating change. Social cognitive theory emphasizes self-efficacy, or a person’s belief in capability for behavior change. The student team wanted to create content that encouraged people and convinced them that they were capable of changing their health behaviors. They recognized that health and nutrition information can be overwhelming and people can quickly become discouraged, so they focused on habit formation and lifestyle modification research that emphasized starting small, being consistent, and managing goals and expectations.

It was also important to the team to provide information that was evidence-based, and they wished to avoid providing medical advice. With this goal in mind, they searched for reliable sources to reference. At the same time, they recognized that Plenty!’s patrons have a limited budget, limited time, and a limited pantry. In order to avoid the burden of too much information, they kept their writing concise. The team looked at everything they did from the patrons’ perspective: “I don’t have 20 different spices. I only have these five. How can I prepare these recipes? How do I eat healthy if I have a habit of drinking six sodas a day?”

A few of the topics that were included in the newsletter included DASH diet, diabetes-friendly diet, healthier holidays, healthy snacks, and meal planning, Mediterranean diet, reading a nutritional label, and avoiding “fad diets.” They also provided recipes and COVID-19 food safety topics.

The final deliverables to Plenty! were comprehensive COVID protocol reviews, both in simple and more detailed formats, as well as picture-based newsletter content in document-format for Plenty! staff to incorporate into their newsletters, handouts, and online, covering COVID food safety information and nutrition education.

Due to the pandemic, the team was not in close physical proximity to each other. They quickly learned how to work well using Google Drive, email, and weekly video conference meetings. Course instructor Dr. Sophie Wenzel summed it up by saying, “I think these are great lessons learned. You all did a really good job of adapting, rolling with it, and making the best out of a hard situation.”

Sarah Legg - DVM/MPH student - Infectious Disease concentration

Sibylle Thaler - MPH student - Public Health Education concentration

Sarah Work - MPH student - Infectious Disease concentration

Sarah Legg, Sibylle Thaler, and Sarah Work partnered with First Responder Canine (FRK9) for their Integrative learning Experience, a nonprofit organization that provides service-bred dogs to first responders that have incurred life-altering injuries, including PTSD, traumatic brain injuries, and mobility disabilities. FRK9 also places dogs within first responder (FR) departments where they’re assigned to a peer-support officer that utilizes them to assist with de-escalating stress and anxiety in the department, during victim interviews, and in community outreach.

In order to expand their program, FRK9 wanted to research the impact that the canines were having within the first responder departments, with the hope of publishing this information to reinforce the use of these therapeutic canines in support of first responder mental health. All of FRK9’s canines are named in honor of first responders. Pictured here is FRK9 Eric, named in honor of lieutenant Eric Eslary, a 17-year police veteran killed in the line of duty.

After discussions with FRK9 psychologist, Dr. Meredith Romito, the student team developed two main study objectives for their project. First, they wanted to understand the effects of occupational stress on first responder mental health, and second, they wanted to assess the need for a therapeutic canine at the Arlington Police Department during the COVID-19 pandemic and time of civil unrest.

The group found that one of their most important goals was to effectively communicate with each other and with their external stakeholders, mentor, and faculty during a time of social distancing and civil unrest. Especially challenging was that the group members were traveling and residing in different time zones. Another goal of the group was to incorporate the knowledge gained from their public health education to develop an effective needs assessment tool specific to first responder departments that FRK9 could refine and implement in the future.

When researching first responders, the team found that there were significant mental health problems within the workforce. While first responders provide essential services to society, their work places a heavy burden on their own psychological, physical, and social wellbeing. This burden increased dramatically with the onset of COVID-19. In addition, the United States (U.S.) is in a state of civil unrest, and police officers are experiencing negative public opinion and dangerous scenarios. The student team found that first responders are exposed to work-related stress and traumatic events that can lead to health problems and even PTSD. Prolonged occupational stress in police officers can lead to burnout, higher risk of cardiovascular disease, increased depression rates, and sleep problems. The National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety found that the workplace suicide rate for protective service occupations was 3.5 times greater than the overall U.S. workforce.

While first responder departments are trying several approaches to help with processing traumatic experiences and to offset occupational stress, FRK9 seeks to provide trained service canines to improve coping strategies and support mental health in first responders. Therapy dogs are used successfully in hospitals, courtrooms, and nursing homes to help patients, children, or individuals with disabilities. While working dogs are well integrated into police and rescue operations, military, and fire stations to help soldiers and first responders in crucial parts of their work, it’s a novel idea to use the help of therapy dogs to support first responders in managing stress and overcoming work-related traumatic experiences, and it’s one the team believes will be effective.

The team’s first step in helping FRK9 evaluate and support a canine intervention at the local police department was to secure IRB review for a research study and to begin the literature review to find evidence-based instruments for pre- and post-survey to evaluate first responder mental health, perceived stress, attitude toward canines, and coping techniques. The group performed internal review for background information on first responder mental health and the effects of occupational stress exposure on health. They also researched the use of canines in the literature and the benefits of the human-animal bond.

After IRB approval, the pre-survey was disseminated by Dr. Romito via a scripted email that included a Qualtrics link to the survey, with approval of the leadership of the Arlington Police Department. The webinar was sent to FRK9 to be used and distributed at their discretion. The pre-survey was distributed to the Arlington Police Department at the same time that a new service dog in training was placed within the department. The team gathered the results of the pre-survey and began to look for trends. Based on the response on COVID-related questions asked in the survey, the students saw the need to create a webinar, Staying Safe During COVID-19. They also created a detailed report for FRK9, summarizing their findings and outlining future suggestions.

In their effort to establish the overview of the department, the team offered an abbreviated survey of both depressive and coping questions. There were two main considerations for this. They feared that the survey would be too lengthy if they included all of the questions regarding both COVID-19 and attitudes toward the dogs. They were trying to keep survey completion time under 10 minutes, and the depressive inventory alone can take over 20 minutes. Importantly, the full inventory included some questions that could be triggering for those suffering from depression or PTSD. Since they were distributing the survey via email for respondents to complete at their convenience and were not onsite, they couldn’t assure that proper mental health support would be available.

The team calculated a composite mental health score based on responses to several questions related to mental health and PTSD criteria in the survey. One of the questions, for example, was, “Does it take extra effort for you to go to work?” Answers included, “I can work as good as before,” “It takes extra effort to get started,” “I have to push myself very hard to do anything,” and “I can’t do any work at all.” The team noted that roughly one-quarter of respondents reported no change, but 50% showed an increase in one or more of the questions, and 25% experienced very poor mental health.

One of the most important statistics the students thought they could provide to FRK9 was whether there was any relation between mental health score and desire for a dog. The mental health score was assigned from 0 to 13. The students divided the mental health score into two core groups to find the risk ratio, a 0 to 3 group and a 4 to 13 group. They found that respondents with a mental health score of four or over were 1.4 times more likely to want a dog than their counterparts with a score of three or under.

The team then wanted to investigate when first responders felt the canine would be most useful: as a recommendation to peers, during debriefing, after a crisis, during a crisis, or as part of visits, just for fun. They found that first responders were most likely to recommend the support canine to a peer and less likely to use a support canine for a debriefing or during a crisis. This was somewhat of a surprise to the group, as they thought there would be a high demand for a therapeutic canine during such stressful situations. Perhaps using the canine during a crisis seemed too overwhelming to the respondents, but there has been success in other first responder departments using the canine during debriefings. The team feels that once first responders at Arlington Police Department have had the chance to see how the service canine is fully integrated, they may change their opinion. The team plans to assess this during follow up with their post-survey.

Literature has shown that historical events comparable to the current civil unrest have had far-reaching effects even in departments not associated directly with an event. For example, the attacks on September 11 had long-lasting negative mental health outcomes for first responders in departments in and near New York City as well as departments in and around Arlington. Interestingly, there were also found to be long-term effects observed in departments in other major, more distant cities like Boston and Chicago. Therefore, to understand where the canine would be best utilized across different departments, the team recommended distributing the pre- and post-survey to departments in different geographic locations, perhaps even areas not experiencing large anti-police demonstrations.

The team feels this information has provided a good baseline for the mental health of the first responders at the Arlington Police Department. Since they were unable to distribute the follow-up survey, they wanted to give strong pointed recommendations for future work. Their first recommendation was to distribute the follow-up survey. They felt that sending out the second survey after only a few weeks would not be representative of the impact a service canine could have on a first responder department, so they recommended waiting to send out the follow-up survey until more officers were able to have contact with the therapeutic canine. Weekly handler surveys are already distributed to gauge interactions that the dog is having, and these can help inform the best time to distribute the follow-up survey. As FRK9 expands into different departments, the students plan to add coded identifiers to the pre- and post-surveys so that more detailed statistical analyses can be run between the pre- and post-surveys.

The team compiled the information from the pre-survey with the Arlington Police Department and outlined a plan for future research within their report. They were able to establish a baseline and a time that will shape first responders for years to come. With over 90 respondents representing a diverse background, they believe they captured an accurate picture of the Arlington Police Department. This baseline allowed them to make stronger recommendations for future research. When this research is complete, the team hopes it will expand FRK9 and advance their ultimate goal of reducing the burden of mental and physical health problems in at-risk first responder populations. Additionally, their webinar provides relevant COVID-19 information specific to first responders, FRK9 handlers, volunteers, and service canines. This webinar provides the most recent public health education material important to staying safe during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The team feels that the deliverables created for FRK9 will contribute to improving the occupational wellbeing for first responders. The survey will help gather mental health information before and after the therapeutic canine intervention and will allow the team to determine if there is a change in mental health over time with the presence of a service dog on staff. If they can prove that the canine does improve mental health and decrease stress in first responders, it will help establish therapeutic canine support as a valid and accepted intervention for high-stress workplaces such as police departments or fire stations.

Emily Hardgrove - DVM/MPH student - Infectious Disease concentration

Megan Toms - DVM/MPH student - Infectious Disease concentration

Elizabeth Hines - DVM/MPH student - Infectious Disease concentration

Shawn Kozlov - DVM/MPH student - Infectious Disease concentration

For their Integrative Learning Experience, Emily Hardgrove, Megan Toms, Elizabeth Hines, and Shawn Kozlov, developed a survey for Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine (VMCVM) to distribute to small animal practices in Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, and DC areas in order to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. VMCVM will be able to use the information collected to inform recommendations on how to better serve as a resource for the regional veterinary community during both times of normal operations and times of crisis.

The goals of the team’s project included assessing the response of veterinarians and staff during the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, prior to the issuance of veterinary practice specific guidelines from the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). For purposes of this project, they defined that time point as April 1, 2020, which also aligns with the stay-at-home orders for Maryland and Virginia.

The students were interested in this time period and the actions that veterinarians took before receiving formal guidance, because they wanted to assess what, if any, actions veterinary staff were taking during a time of changing public health opinion and tumultuous and contradictory media coverage. The group also wanted to assess what resources veterinarians and their staff relied upon to help them make decisions related to COVID-19 so that they could structure recommendations for their stakeholder, VMCVM, to assume a leadership role in the community and facilitate communication, both now and in future times of crisis. Finally, and partially for their own interest, the students wanted to determine the risk perceptions of veterinary staff in relation to COVID-19 and assess the impact of practice policies and protocols on that assessment.

In order to start answering these questions, the students distributed a voluntary survey to their population of interest, which they limited via screening questions at the beginning of the survey to small animal veterinary practice staff, including vets, techs, office managers, assistants, and administrative staff in Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, and DC. The team structured their survey to provide information on each of the topics of interest mentioned. Their ultimate goal was to use the information to create a series of recommendations for VMCVM on what resources the regional veterinary community most wants. Their goal was to assess the communication needs of the small animal veterinary community and provide those results to VMCVM in support of the public health principles of assessment, assurance, and policy development.

For the assessment component, the team asked survey questions about changes to veterinary practice procedures in relation to the pandemic. For policy development, they mobilized community partnerships by partnering with VMCVM and regional VMAs to deploy the health survey, and they will share the results through similar routes. The culmination of the project will result in the formation of an information-sharing platform that should empower veterinary practices to adjust during future crises and operate safely and effectively.

Regarding assurance, the platform will provide information specific for veterinarians and veterinary staff responding to crises when other information may not be available. It will help assure a competent health workforce, and it will help evaluate the effectiveness, accessibility, and quality of personal and population-based health services by investigating the sources that veterinary practices relied upon prior to the stay-at-home orders and the widespread availability of specific guidelines and evaluate whether they still think that there’s a gap in information related to safe practices during the pandemic, overall trying to help create useful information for VMCVM.

At the beginning of the project, there was no scientific literature on this topic. However, in the intervening months, there were several relevant items published. The most notable of these is the AVMA survey of COVID-19’s impact on veterinary practices, available online in an interactive dashboard format. The AVMA survey was fielded in April 2020 and received 2,017 responses from AVMA-registered veterinarians. It assessed a variety of topics such as precautions implemented in practices, impact on business-related measures, changes to client interactions, inventory factors, concerns of employees and clients, sources of information utilized by the practice, and how the AVMA can better support veterinary practices with relevant information.

According to the AVMA survey results, more than 80% of practices turned to the AVMA for information during the pandemic, followed by state veterinary medical associations. When asked how the AVMA can support practices, the top two responses were ”providing consistent updates” and “guidelines for safe operating procedures.” In light of the AVMA survey results, the team altered several of their questions in order to be better able to compare the responses from their regional survey to the AVMA’s responses from its nationwide survey. The team also incorporated the AVMA survey results into their recommendations.

The ILE project began in February 2020, at which time the team’s initial plan for the survey was to focus on occupational health and wellness in their target population. The pandemic and its effects caused them to shift their project topic to examine the impacts of COVID-19 on small animal veterinary practices. From February to late-June, the team revised and improved their survey. In late June, they submitted their final survey to the IRB. After obtaining IRB approval in July, they sent the survey out through the alumni network, state veterinary medical associations, and emails to the VMCVM referring veterinary network. They collected their survey on July 30 and analyzed their data utilizing a mix of RStudio, JMP Pro, and Excel before putting together a report for stakeholders. The team’s deliverables were the survey, the analysis of the data, their recommendations for resource creation, and their final presentation.

To get a baseline idea of what their respondent population was doing early in the pandemic, the students collected information on the actions undertaken by veterinary clinics prior to April 1, 2020, which was a week or so prior to the issuance of CDC and AVMA guidelines. Overall, their results indicated that people were making changes to their practices to conserve PPE, increase social distancing, and implement precautions to high-risk staff.

The team found some concerning results from their survey respondents that were not consistent with current guidelines. Prior to April 1, 2020, fewer than 25% of respondents were screening employees for symptoms of fever prior to their shifts, screening pets for exposure to COVID-19 (though 30.3% of clients were being screened at that time), requiring social distancing in the lobby, replacing in-person staff meetings with video or teleconference when possible, splitting practice employees into smaller teams and limiting contact between teams, constructing a thorough employee safety and health program based on workplace risk assessment, and including the possibility of occupational illness or developing a written infection control plan.

The team found that their results appeared to mostly agree with the results of the AVMA survey, although they saw higher rates of respondents, greater than 75%, conducted phone or online billing, required sick employees to stay home, and performed contact-limited or contact-free distribution of prescription foods or medications. This is compared to the AVMA rates, which were around 50-60%.

Several resources became available during the early weeks of the pandemic, and the student team wanted to evaluate which resources the veterinary community was aware of and which resources were implemented. More than 50% of respondents were aware of the AVMA flow chart and the CDC interim guidelines for veterinary clinics, while only 38.5% of respondents were aware of the veterinary college’s emergency operating procedures that were published online. The odds of alumni being aware of the VMCVM emergency operating plan (EOP) were 1.75 times higher than non-alumni.

The team found that the AVMA comparison provided a good example of sample biasing. Only 29% of the students’ respondents said they relied on AVMA for information, as compared to some 90% of the AVMA respondents. Aside from a fun lesson in error, this provided the team with support for the claim that veterinary staff have not been relying only on one particular source of information during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The team found that their results were not skewed as heavily toward the left as the AVMA results, nor did they see any sources that were relied on by 50% of respondents. According to their results, the most relied upon sources of information were the state public health government officials, federal public health officials, the AVMA, state VMAs, and peer-to-peer networks, all around 22.8-31.6% of the respondents.

The team further investigated the helpfulness of various resources. Ease of accessibility and sample EOPs and documents were ranked very helpful by the most respondents, suggesting that these are important ways to direct future efforts. Forum-like function and active moderation were ranked not helpful at all most frequently by respondents, suggesting these resources should take lower precedence in future efforts.

In order to additionally assess what resources to focus on during an emerging crisis, the group compared the helpfulness of the type of resource. A town hall was most frequently rated very helpful, whereas a web forum and call line were less highly rated. The mobile app had the least frequent very helpful rating.

In the AVMA survey, responses to the question, “What can the AVMA do to support you?” were the lowest for an idea-sharing forum, further supporting that this may be less of a priority. Based on these results, focusing on a town hall could be more beneficial than these other alternatives during initial crisis response. It also may be more important to focus on because it is a more specific and community-focused resource that the college can offer that larger organizations would not be able to facilitate. The AVMA did not include hosting a town hall as a possible resource in their survey, further supporting that this is a gap in resource availability.

The team collected a significant amount of data beyond what was immediately relevant to their stakeholder. They plan to analyze that data for eventual publication. Among this data was more demographic information, including the occupation of the respondent. They were particularly interested in whether technicians, administrative staff, veterinarians, and other staff members might have differing responses to some of these categories.

The team also collected a significant amount of risk perception data including proportion of respondents for each possible response bracket, conveying the level of concern over being exposed to COVID-19 due to their boss or manager’s actions or their clients actions, concern over experiencing severe complications, being exposed due to their coworkers’ actions, being infected at all, and being exposed due to their own personal practices as well as their concern of transmitting COVID-19 to others. They found potentially interesting relationships to examine in the data, including the apparently visually low concern over one’s personal practices leading to exposure and the high faith placed in the bosses and managers of our respondents’ practices. The team intends to look further into how that compares to the reported occupation and ownership status of the practice, and they suspect potential issues of confounding.

In the VMCVM mission statement, the college seeks to protect and enhance animal, human, and environmental health and welfare through the creation, dissemination, and application of new medical knowledge via discovery, publication, education, and engagement. To help the college fulfill this mission when making recommendations, the students wanted to examine what types and traits of resources would be most helpful during an emerging crisis as well as how to best take advantage of the college as a referral hospital and utilize its strengths as an already established resource for expertise in the community. During the initial stages of a crisis, focusing efforts on a town hall, or multiple, would be incredibly beneficial in engaging stakeholders and the community. It would also be more locally specific and community driven, more so than other larger organizations, such as the AVMA.

A town hall would also be a way to increase the visibility of the school’s EOPs. Such documents were ranked highly as potentially helpful but not as highly in terms of visibility or use by respondents. Beyond initial crisis townhalls, there are other avenues that the college could take to increase the school’s visibility as a resource during crisis response. The college could increase the frequency of communication to external stakeholders through weekly, biweekly, or monthly newsletters that would address relevant updates, convey new information, and share opportunities for upcoming events and informational sessions or town halls. This could also build upon alumni and referral listservs, as the student survey did find that alumni had almost two times the odds of being aware of the college’s EOPs but were not significantly more likely to use them. This indicates they are an important group to continue to target.

This survey is also timely, as the college’s website is currently being revamped, and the findings could help direct the inclusion of easily accessible and visible EOPs and other important updates. The results of this survey also highlight that the college should consider engaging more highly in the valuable resources and expertise of public health agencies and VMAs frequently, given the distribution of resource use among our respondents. It might be beneficial to have these groups communicate more regularly to produce content for their stakeholders and membership that is both consistent and cohesive. This survey in future areas of investigation could further inform the creation of a general survey to be disseminated to veterinarians or public health workers during times of crisis, and this would also be an opportunity to address some of the limitations of the survey.

The student team also outlined potential limitations of experimental design and factors that could have led to bias in their results. First of all, their study population was limited to primary brick-and-mortar small animal practices and not the entire scope of the veterinary community. Additionally, there is no way to know if their sample size was representative of a population they sampled, and they don’t have an estimate of all of the veterinary staff in the four areas surveyed. Additionally, emails primarily went out to veterinarians who the team then relied on to further distribute among their work. However, of the 234 valid responses, they had a relatively smaller number of non-veterinarians respond to the survey.

An additional bias was the voluntary nature of the survey. Of further note, during analysis, the students did combine all non-veterinary positions into one group for analysis in their two-by-two tables. This masked any differences in veterinary technician, practice manager, or other groups that may be significant. They also combined responses to some of their Likert questions addressing concern and risk assessment due to improper matching of survey answers.

Although their survey did have limitations, they believe that sharing the results will provide valuable information on crisis response. To increase awareness of their findings, the team will be distributing a video presentation of the results to be shared across email, social media, student VMAs, and on their website. The students also hope to ultimately publish a manuscript to further make the findings available.