New MPH culminating experience provides professional development for students while supporting local organizations

On Wednesday, May 13, 2020 graduating students from Virginia Tech’s Master of Public Health (MPH) degree program presented their Public Health Integrative Learning Experience (ILE) projects. The ILE is a culminating experience option that fulfills the requirements of the MPH degree. A team of two to four MPH students spends the semester working on a project that benefits an external organization. Students further develop knowledge and skills in foundational public health areas as well as in their chosen MPH concentration (i.e., infectious disease, public health education). The students’ ILE projects showcase our program’s signature areas of One Health and rural/Appalachian health.

The spring 2020 semester was the first semester in which standalone degree-seeking MPH students completed the ILE as their final academic deliverable. Prior to the adding the ILE as the MPH program’s main culminating experience in fall 2018, the program solely had a Capstone culminating experience option where students worked with their individual faculty advisor on an academic paper that integrated public health skills acquired in the classroom and their practice experiences to approximate a professional experience. This option is still available for simultaneous degree students (e.g., PhD/MPH) where the Capstone brings a public health aspect to their disciplinary work.

Dr. Sophie Wenzel, Assistant Professor of Practice and Associate Director of the Virginia Tech Center for Public Health Practice and Research, is the ILE course instructor. Dr. Wenzel reflects on the ILE experience for all involved: “This is really a win-win: students get to refine and practice their public health skills while working closely with a community partner on a meaningful and needed project. We are fortunate to have a small program with excellent relationships with community partners that allows us to provide this type of culminating experience to our students.”

By clicking the tabs below, you can view a writeup about each ILE team’s project from the spring semester. The ILE projects were all impacted by COVID-19, yet the students persisted. Students were asked to pivot to working remotely in a very short time frame. The students adapted their schedules, deliverables, and communication methods to deliver high quality, meaningful deliverables that will serve their community partners. The program looks forward to continued engagement with these partners and new ones to provide these organizations with support while further developing our students’ professional skills.

MPH students Jordan Mills, Aimee Smolens, and Samantha (Sam) Seay partnered with external organization, Virginia Department of Health’s New River Health District (NRHD), on their project entitled “New River Health District Employee Wellness Initiative: A Three-Point Approach to Workplace Wellness.”

Using an employee wellness needs assessment that team member Sam Seay completed in summer 2019 for her individual Public Health Practice Experience, the team identified four priority health topics for the group: physical activity, emotional health and mindfulness/self-care practices, healthy eating habits/healthy cooking and shopping tips, and stress management. Using these topics, they created goals for creating a NRHD wellness plan: to encourage NRHD employees to prioritize their health and focus on time management, to increase employee knowledge and skills related to health topics of interest, to increase employee participation in wellness activities and strategies, and to assist NRHD to become worksite certified through CommonHealth.

Utilizing the Stages of Change Model (i.e., building a progression of small steps to progress toward a larger goal) and the AMSO Framework (i.e., a worksite wellness model), the team developed a variety of initiatives, such as monthly lunch-and-learn gatherings, an eight-week nutrition challenge, monthly wellness newsletters, and “throne zone” informational posters to be displayed in NRHD restrooms. To provide encouragement and incentives to participate, the student team sent out bi-weekly emails, offered participants the ability to opt-in to receive short informational text messages, provided free lunch with the lunch-and-learn component, and secured four hours of recognition leave to be awarded to the nutrition challenge winner.

The eight-week nutrition challenge focused on providing healthy eating/healthy cooking and shopping tips. The participants were challenged to complete bi-weekly tasks that were created with guidance by the WellSteps campaign. As part of the challenge, participants were encouraged to eat more fruits and vegetables, substitute healthier meals for less healthy meals, track calories, and create and follow a meal plan.

The lunch-and-learn component consisted of educational presentations covering the priority topics revealed in the needs assessment: stress management and time management, nutrition and meal planning, and exercise and physical activity. The student team presented three 30-to-45-minute educational presentations that provided opportunities for skill building. The first presentation was offered in three modes: in person at the health department, via Polycom, or viewed electronically afterward. For the in-person and Polycom attendees, a free lunch was provided to incentivize participation. Presentations number two and three were available only in electronic format due to COVID-19 in person restrictions that were put into place during that time.

To assess results, the students developed an 11-item pre-and post-test using SMART learning objectives to measure improvements in knowledge. Of the participants that completed the tests, the results revealed a significant increase in mean score before and after the presentation, which suggested an increase in knowledge gained after the educational material was delivered.

The group also made suggestions for the NRHD’s own wellness team to use moving forward. They recommended that the team create a central email for the NRHD wellness team to reduce confusion among employees. For future lunch-and-learns, the students suggested that the team decrease the frequency and duration to reduce the cost and time burden. The NRHD wellness team can also use the recorded video presentations from the lunch-and-learn sessions for future lunches. The students also recommended that NRHD continue to partner with future Virginia Tech MPH ILE student teams to develop additional content for lunch-and-learn presentations.

To reduce the time burden of creating materials to support these initiatives, the student team developed easy-to-use templates for the next 12 months of monthly newsletters and throne zones. They also created six wellness challenges for the wellness team to implement in the future, including a gratitude challenge, a share-your-lunch challenge, and a reading challenge.

Dr. Pam Ray, the student team’s ILE external stakeholder mentor at NRHD, expressed great appreciation to these students. “When things calm down [in reference to NRHD’s COVID-19 response], we can go in and rejuvenate what they’ve offered us. They certainly have made our job easier to use their templates to continue the work that they’ve done. So, we definitely are going to be moving forward with this. I guarantee you that if this had not been started, we would not be getting anything done for our own wellness.”

MPH students Lauren Buttling, Katherine (Katie) Eisner, and Emilie Schweikert completed an ILE focused on evaluating the anticipated public health impacts due to climate change for the town of Blacksburg. They started off with a primary literature review to identify the overall top five public health impacts due to climate change. From there, they developed a technical report to present to the town’s climate vulnerability assessment team.

The student team’s main goal was to evaluate the range of anticipated public health impacts of climate change by mid-century and end of century under a single emission scenario as well as an assessment of the town’s adaptive capacities for each of these health impacts. Their objectives were to analyze climate data and interpret downscaled climate modeling for geographic and temporal scales, to assess public health implications of anticipated changes to the local climate, to assess public health implications of broader changes to climate (national/global), to evaluate and rank public health risks related to climate change as a first step to identifying adaptation practices and policies, and to develop technical report and presentation for the Town of Blacksburg.

The overarching context of their project was the observation from a number of major public health organizations, including the American Public Health Association, that climate change is becoming one of the greatest threats to public health for the coming century. One of the leading global bodies of experts on climate change, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, has estimated that even if all nations adhered to the standards necessary to keep global warming under 1.5 degrees Celsius, climate-related risks to health, livelihood, food security, water supply, human security, and economic growth are still projected to increase. The Commonwealth of Virginia is no exception to that. A body of concerned physicians, Virginia Clinicians for Climate Action, has noted the potential health impacts of climate change to be hundreds of lives lost and billions of dollars if action is not taken.

Heat Stress

Heat stress was one area of focus for the student team. Their research showed that the southeast region of the U.S. is known for warm, humid weather. Historical trends support an overall warming since the 1970s, with average daily minimum temperatures increasing three times faster than the daily average maximum temperatures. These trends are expected to continue, along with increased duration and frequency of heatwaves, a longer freeze-free season, and a doubling of cooling degree days (the days we anticipate needing air conditioning or other means to cool our environment).

Heat-related events are actually associated with the highest cumulative deaths of all extreme weather-related events, including hurricanes and tornadoes. Anticipated public health impacts include acute illnesses like heat stroke and heat stress; exacerbation of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine, and renal disorders; and an overall increase in hospital admissions and all-cause mortality.

The student team’s recommendations for preparing for rising temperatures included developing or expanding a heat action plan, implementing early heat warning systems, increasing access to cooling, offsetting outdoor work or play schedules, establishing systems for checking on vulnerable populations, and initiating possible climate sensitive construction or city planning.

Air Quality

The second public health impact the student team focused on was air quality. Air quality is impacted by air pollution. Higher greenhouse gas emissions lead to increases in both ozone and particulate matter pollution, and carbon dioxide levels lead to increases in pollen. Each of these types of air pollution can irritate the lungs, and this is particularly problematic for people who have chronic respiratory illnesses, such as asthma and allergies.

Additionally, both ground-level ozone and particulate matter air pollution are associated with increased rates of asthma attacks as well as increased hospital admissions and emergency room visits for asthma. Increased pollen also leads to more severe allergy symptoms, and this is associated with decreased school and workdays and productivity.

In looking to the future on how air quality may be impacted, the student team found that under a high emission scenario, Blacksburg may fall within the high to very-high risk range of tree pollen increase. As of 2019, Blacksburg’s air quality index was 74, with 100 being the best. This is considerably better than the US average of 58. Blacksburg also has a lower risk of respiratory illness than both the state and the country. However, vulnerable populations such as children, the elderly, people with pre-existing respiratory conditions, and outdoor workers are still expected to experience higher vulnerability and higher risk.

System recommendations the student team had for addressing air quality in Blacksburg were to continue monitoring the air quality index, ozone, and pollen levels and to issue warnings for public spaces when they are at high levels, particularly for areas with high densities of vulnerable populations (i.e. schools and nursing homes). The team also recommended protective measures for outdoor workers who face occupational exposure and assessing the burden of disease in order to plan for emergency and primary care due to asthma and allergies. Promoting active modes of transportation can limit overall traffic pollution in the town, and increasing health education awareness of personal protective measures to limit individual exposure could also be an important strategy.

Food Security

Another implication of climate change that the student team looked at was food security. Climate change is expected to impact all four dimensions of food security: availability, access, utilization, and stability. Rainfall variability and warmer temperatures can reduce the availability of food and make it more expensive. Extreme weather events can disrupt the supply chain and make transportation of food to grocery stores and other areas more difficult.

Higher carbon dioxide and heat levels are both associated with overall decreased agricultural productivity as well as decreased nutritional value due to lower protein, zinc, and iron content. Globally, climate change is expected to reduce agricultural yields in many places. The southeastern United States could experience a 15-25% decrease by the 2080s.

The student team anticipated that the primary impacts from climate change on food security in Blacksburg will be in the areas of access and utilization in the form of higher food prices and reduced nutritional value. In 2017, for all of Montgomery county, the food insecurity rate was 13.8%, which is about 2% higher than the U.S. average. Individuals who may face additional barriers to food insecurity include those who are poor and low-income, pregnant and nursing women, minority populations, and those with specific dietary requirements.

Some recommendations the team had for addressing food insecurity included developing a food security assurance plan to ensure access and increasing capacities of assistance services like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in order to increase their serving ability. They also suggested promoting nutrition education (e.g., following a healthy diet, adhering to a food budget, reducing food waste) and prioritizing those vulnerable populations that would face additional barriers to food access.

Infectious Disease

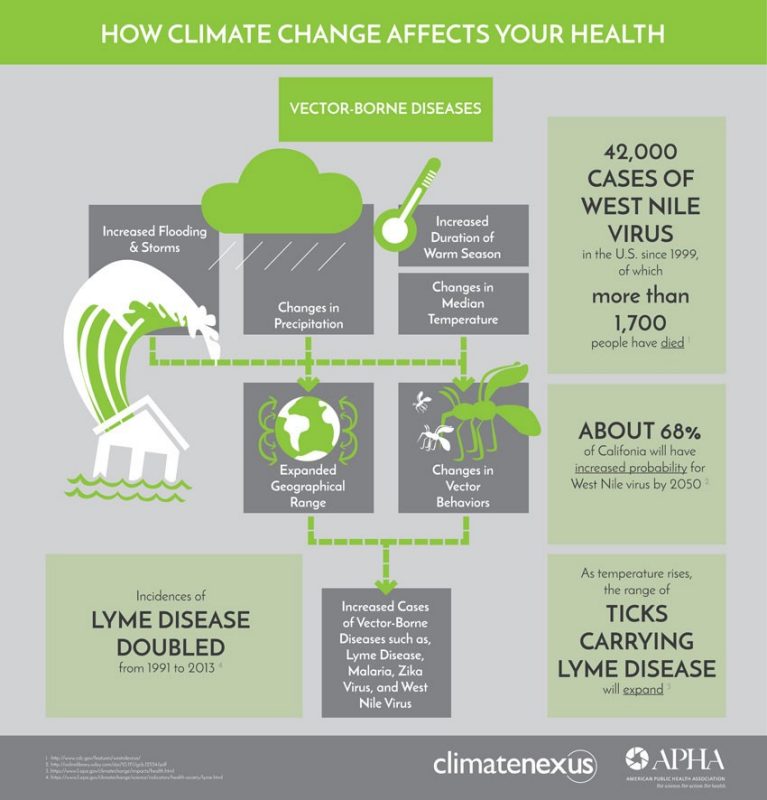

The students also identified that infectious diseases will be impacted by climate change, specifically vector- and water-borne diseases. There are currently three Virginia Department of Health sponsored mosquito surveillance areas in Virginia. Surveillance in these areas include monitoring the number of mosquitos, species, and diseases being transmitted in Fairfax County, Norfolk, and Richmond from May through October each year. At all locations, mosquitos were shown to be actively carrying West Nile virus. Eastern equine encephalitis was also found in Norfolk.

West Nile virus is the most prevalent mosquito-borne disease in the United States, with cases occurring in the warmer months of summer through early fall. The team’s research found that this transmission season is expected to increase with climate change. Eight out of 10 cases result in no symptoms, but those that do have symptoms can exhibit febrile illness like fever and rash. Symptoms can also be neurological, causing meningitis or encephalitis. Encephalitis is infection and inflammation of the brain and symptoms can include convulsions, paralysis, and numbness. The disease is maintained in the environment by being transmitted between vectors and birds. There can be spillover to horses and people.

Eastern equine encephalitis has the same exact transmission cycle as West Nile virus. However, it can cause much more severe disease and more cases are symptomatic. There is a mortality rate of 30%, and that occurs usually within two to 10 days of symptom onset.

The team also identified dengue virus as a possible novel virus occurring in the region. The World Health Organization shows the upper boundary of the virus as being below southeastern Virginia. The team expects that the suitable environment for the vectors of dengue virus to now be found in southeastern Virginia due to climate change. This disease can have mild presentation of nausea, vomiting, and rash and is also very well known to cause the painful break bone fever.

When treated, severe dengue has a mortality rate of 2-5%. The team is concerned, however, that when dengue is left untreated, possibly in areas where the disease is not common, mortality rates can be as high as 20%. The team expects that between 2020 and 2050, dengue could be transmitted locally during summer months in our region.

They also identified that tick-borne diseases will see an increase. While ticks can overwinter and survive frost days, frost days do significantly reduce the population. The models show that by 2050 southwestern Virginia will be increasingly suitable for the vector of Lyme disease -- and then consistently suitable throughout the year by 2080. Additional models show that by 2050 all of the counties in southwestern Virginia will be highly suitable for the vector of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever.

The student team identified water-borne diseases as possibly seeing an uptick in cases, as most of the regional water and sewage treatment infrastructure was built for the climate of the period in which it was built and may be ill-equipped to deal with increased precipitation and temperature. Very severe storms resulting from climate change (storms that rank in the top 20%) are associated with most of the water-borne disease outbreaks, such as E. coli, salmonella, leptospirosis, and other diarrheal diseases.

The student team recommended vector monitoring and disease monitoring past the typical May to October timeframe. They also suggested that the town partner with the local health department, state health department, and academic institutions to monitor these areas to do genomic testing of pathogens. Local governments should also monitor the spread and incidence of climate-change-associated diseases as they are reported at a county level. Education of local healthcare providers on insect vectors in the region and local transmission of novel diseases is important, as well as identifying well-water users and providing targeted education to them on the potential risk of flooding.

Emergency Preparedness

The next area the student team focused on was emergency preparedness. Extreme weather events are anticipated to increase with climate change. In Blacksburg, the student team’s research showed this primarily as increased flooding due both to increased precipitation and increased Atlantic hurricanes. The public health impacts of this increased flooding include acute injury and death, unsafe home and work environments, and potential exposure to hazardous or infectious material. The students also found the potential for increased mental health problems as we deal with more dramatic experiences and events.

Historically, Blacksburg does have some vulnerabilities to flooding. There are three streams that are sources of inland flooding: Tom’s Creek, Stroubles Creek, and Cedar Run. In the last century, Blacksburg has had six severe flood events, a few of which have cost millions of dollars in damages. Additionally, there are eight hazardous waste material sites that are within or near the limits of the town that would be cause for concern in the event of severe flooding.

Fortunately, Blacksburg has already taken quite significant steps to prepare for flooding, including establishing zoning regulations and building codes that protect vulnerable individuals and properties and establishing flood insurance rate maps and flood insurance policies. The stormwater management system in Blacksburg is also well beyond Virginia’s state requirements. Finally, Blacksburg has a local branch of the national weather service, which helps augment their early warning and communication systems for flooding events.

The student team had a few additional recommendations, which centered around coordinating education to help mitigate illness or injury during these events and routinely assessing critical town infrastructures involved in energy, transportation, healthcare, and communication. They also recommended collaborating with local health systems to organize a stress test of local health care and public health systems so that in the event of an extreme weather event, Blacksburg would be assured of their level of preparedness.

The team’s external partner, Sustainability Manager Carol Davis, was pleased with the work and the recommendations of the team, stating that they were professional throughout their work. “Even when we had to switch approaches midway through, you did an amazing job, so thank you for that.” The student team’s work will help inform future public-facing documents and assist the Blacksburg planning department build their internal risk ranking.

MPH students Catherine (Matty) Meyer, Malik Outram, and Tiange (Jennifer) Wu partnered with Virginia Cooperative Extension’s Family Nutrition Program to develop a policy, systems, and environmental change initiative to improve healthy food access and availability for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)-eligible individuals and families through food pantries located in Virginia. The student team’s role in this project was to provide research deliverables to further efforts in developing and implementing the desired feature initiatives to set the groundwork for transitioning all food pantries in Virginia to move to a client choice format, where food pantry/bank visitors can select healthy food options for themselves.

One of the team’s deliverables was a qualitative data analysis report that resulted from interviewing participating SNAP-Ed agents. Feedback was obtained from the agents on their comfortability with moving to a client choice program. The team found that the agents would like to see more cooking demonstrations and tastings with the food items that are available in the pantries/banks, more community-based support for food pantries/banks, and to further increase community education and outreach, specifically for healthier donation items to be accepted by food pantries/banks.

From the feedback that was received in these interviews, the students developed three recommendations to be included in the change initiative. One was to develop and disseminate a communication plan for all participating food pantries and community partners. This would be in the form of standardizing guidelines across all the food pantries that are involved. Another was to develop and encourage an overall policy for all food pantries/banks as a reference for donation requirements. The agents also asked for the development of a shelf-talker template, which is a form of nudge strategy, to disseminate to each pantry to tailor to items that are readily available in their community foodbank.

The students’ policy analysis deliverable was a summary of current policies from national, state, and organizational levels. It presented current regulations around donated food items for pantries and aided in the development of the policy change for food banks and their donation restrictions.

Another deliverable was a literature review of successful nudge strategies to encourage healthier food options that have been implemented in client choice pantries across America over the past 10 years. The student team included a total of seven programs that had previously evaluated the impacts of incorporated nudge strategies. This report highlighted the success rates and impacts of each nudge strategy that was used to leverage food pantry clients to independently choose healthier foods for themselves.

The students found that moving food pantries/banks to a client choice model allows those being served to preserve their sense of dignity and control. Clients are able to “shop” for their own food, as one would in a typical grocery store setting. Many food pantries currently have pre-selected offerings given to the client without any input about their personal food preferences or needs, exacerbating the lack of flexibility and control that these clients may experience in other areas of their lives.

Another aspect of the students’ project was to develop ways to educate and encourage clients to make healthier choices when self-selecting foods. One recommendation the student team had for the food pantries/banks was to make the healthy food options in the pantries more visible and inviting. They suggested grouping the fruits and vegetables together by color at the front of the pantry for an appealing display. Large, attractive signage to let clients know what the different foods are was also deemed important. Adding signage that encourages “better options” was another recommendation of the team. For example, encouraging the choice of oatmeal by exhibiting signage stating that oatmeal will keep you fuller, longer.

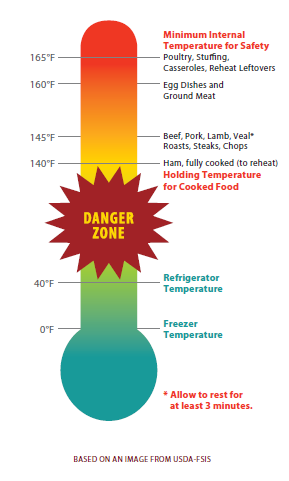

The team’s food safety guideline deliverable provided guidance for food pantries and their clients on how to properly store, handle, and prepare fresh food; guidelines for preventing food-borne illness; and infection prevention information (including COVID-19 information). Since providing fresh food means that items need to be prepared by the client at home, the students considered that many may not know how to store and prepare food properly. Therefore, they included guidelines for both pantries/banks and clients on how to properly clean, store, and cook fresh foods. They provided guidance on the recommended internal food temperatures to prevent acquiring food borne illnesses from listeria, E. coli and salmonella.

ILE faculty instructor, Dr. Sophie Wenzel complemented these students on their work, “The students provided valuable assistance to the Family Nutrition Program by conducting research and developing tools to better serve food pantry clients throughout Virginia.”

MPH students Jenna Eggborn and Sodiq Aleshinloye focused their ILE project on One Health Rabies, working with external partners, Dr. Pamela Ray, Gary Coggins, and Reuel Eddison of the Virginia Department of Health New River Health District (NRHD). This student team built upon the work of previous MPH ILE students Armaghan Nasim, Caleb Whitfield, and Samantha Talley, done in summer 2019.

The 2019 student ILE team focused on assessing the knowledge of rabies in human healthcare professionals in the NRHD by building and analyzing the data from a 25-question survey. They found that human healthcare professionals were not always seeking external consultation when they had a suspected or positive case in their hospital or emergency department and were not always aware of the appropriate post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) schedule and administration site.

As Virginia is consistently in the top five states for rabies confirmation, the 2020 student ILE team felt it was important to continue to learn more about the rabies knowledge gap in our area’s medical professionals. The student team’s goal was to assess the understanding within the medical student community regarding basic rabies knowledge and appropriate procedures for suspected or positive rabies cases. One of the major deliverables for this project was creating and distributing a survey to Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine (VCOM) students and using those results to build a needs assessment.

The students put together a 15-question survey for medical students. They retained many of the questions from their predecessors’ original survey of medical professionals and added in other questions that specifically targeted the medical student community. The survey was completely anonymous, and the medical students would have a 2-week open time to respond.

The student team had significant limitations imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, and they were not able to distribute their survey to the VCOM medical students. They had also planned to present rabies educational content to students and the faculty members at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine Annual Open House, but the event was cancelled due to COVID-19 concerns.

In lieu of distributing and analyzing their survey, however, the students were able to explore a 2011 rabies data set to investigate the patterns in rabies cases in southwest Virginia. They obtained this data from the New River Valley Regional Commission, which revealed the number of confirmed rabies test results in five major cities in southwest Virginia. In terms of confirmed tests, Radford showed 135, Christiansburg had 162, Blacksburg was at 259, Pulaski followed up with 62, and Floyd evidenced 79. Blacksburg had the highest number of rabies investigations , closely followed by Christiansburg. This was thought to be due to the higher population density in Blacksburg and Christiansburg. The data also showed that the area consistently had more negative cases of rabies test, which is a good result. Floyd had the highest case of rabies-positive investigations at 41%.

In 2017, wildlife species represented greater than 90% of rabies cases in the United States. The team looked at the difference in rabies in domestic animals vs. wildlife. The results they found aligns with the national statistics of rabies: total wild animal rabies in our area was 75 cases and domestic animal is 64. The team noted that the greatest frequency of domestic animals with rabies is cats. Floyd was found to have the highest rate of wild animal source rabies. Blacksburg had the lowest negative cases of rabies from wildlife. The 2011 rabies data aligns with 2017 data and can inform the recommendation of policies and rabies educational programming in the future, especially in Floyd, with the highest wildlife cases of rabies.

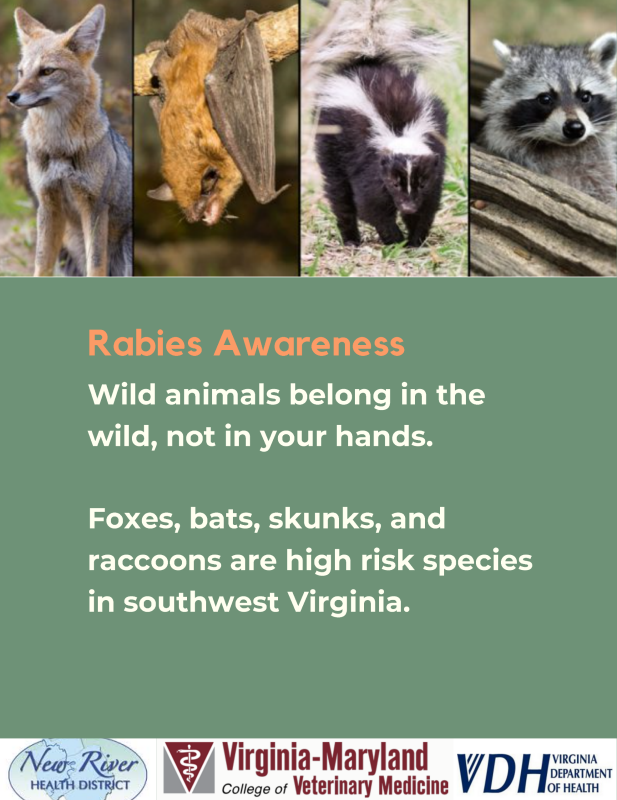

A second priority of the team was the creation of infographic visualizations to increase the public’s rabies knowledge. On average, the NRHD investigates up to 650 animal-bite cases each year, making rabies prevention and education programs a priority for the department. The student team designed infographics for a population-based One Health rabies program through which audience-appropriate public health content could be communicated.

The team’s first graphic targeted workers in the emergency department. Because the emergency department is the first line in the care for individuals that have been bitten by rabies carrier animals, it is important that they know to immediately call the health department. This infographic lists high-risk animals, which include bats, fox, and racoons. It also defines next steps, such as assessing the patient’s vaccination history. Additionally, the team included post-exposure prophylaxis for both previously vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

This second graphic is for visitors to veterinary clinics and advocates rabies vaccination. It encourages people to keep their pets’ rabies vaccination up to date and to avoid contact with wildlife. It also lists the various animals that can carry rabies and entreats people to call the health department or work with their veterinary doctor if they suspect rabies exposure.

Another infographic for veterinary clinics details how to identify the animal involved in the bite and how to assess risk. Importantly, this graphic explains that exposure of your pet to a rabies vector animal does not necessarily require that the pet be euthanized, which is a common misunderstanding that can prevent pet exposures from being reported.

The next design has the goal of raising rabies awareness in those who enjoy hiking, a popular activity in southwest Virginia and one that can increase the likelihood of interaction with rabies-vector animals. This graphic informs that when there’s an exposure or a bite, the first thing you should do is call the health department, then thoroughly wash the wound and seek medical attention. Another version of this design includes precautionary education, stating, “Wild animals belong in the wild, not in your hands.” This is targeting those who might be tempted to play with wild animals. The graphic makes it clear that the first line of action when you have exposure to animals in the wild is to call the health department.

The team’s community mentor, Dr. Pamela Ray, noted that the team “never gave up in spite of insurmountable odds against you. We appreciate your resiliency…You laid some great groundwork for us, and we do appreciate the analysis of the data. I love the infographics. You did a great job, and we’re going to work to get them out, not only on our website, but also out in a print form to go out to all those locations that you talked about. So, thank you very much for all the work you did in spite of the odds.”

MPH students Rachel Burks and Sarah Nguyen completed their ILE project with The Giving Garden, a volunteer organization in Salem, Virginia. The Giving Garden was initiated by a partnership between Salem Presbyterian Church and the City of Salem about five years ago. All of the garden produce is donated to those in need in the surrounding community through partnerships with other local organizations. In the past, garden leadership had expressed challenges in mobilizing and managing garden volunteers, and had also indicated an interest in making sure that the work of the garden truly meets the needs of the community and improves access to fresh produce for those most in need.

The students divided this project up into four main components. The first was to provide a needs assessment to analyze the capacity of potential partners and the fresh produce access within the community. Another was engagement, which included fundraising, marketing strategies, and providing educational materials to the organization. The implementation component involved building organizational capacity and providing recommendations. Finally, there was a food safety component, where the students provided documentation such as food safety guidelines and additional garden information.

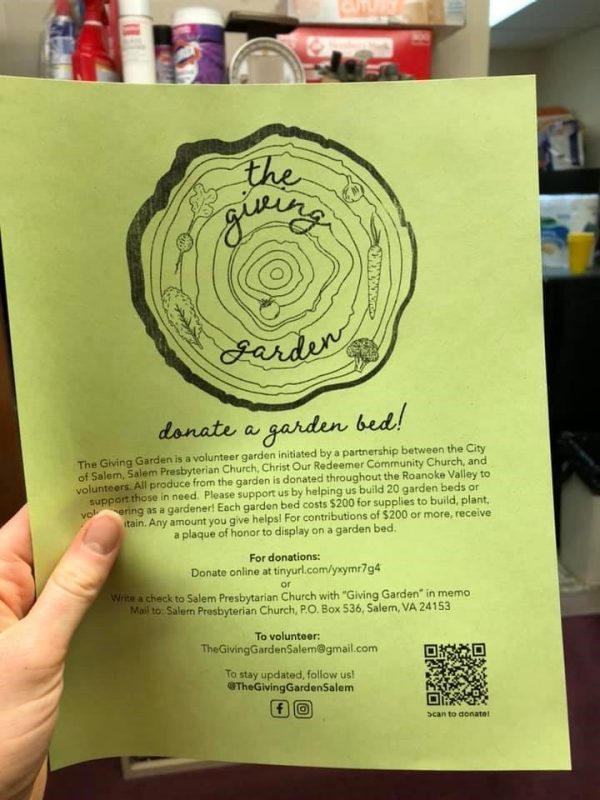

The student team started their work with The Giving Garden by completing a visioning process with the garden leadership team. This resulted in the creation of a formal vision, mission, and goals for The Giving Garden, which previously were not in place. The name, The Giving Garden, was also developed during this process, as was the logo that Sarah created for the garden. The student team supported the development of two working groups around different aspects of the Garden’s mission. One working group was an engagement team, and the other was a construction and garden logistics team.

The students completed a brief assessment of fresh produce access in the greater Roanoke area, which also included an assessment of needs and capacity of potential partners to distribute fresh produce harvested from The Giving Garden. The data from a literature review was used to create an interview guide for use with potential partners. The engagement working group of the Garden created a list of potential partners, all of whom were contacted. Six responded and participated in an interview, and The Giving Garden was provided with a summary of the interview data. The student team also used that data to provide recommendations in the implementation plan.

To identify barriers to fresh produce access by individuals and families with limited incomes, the team used the assessment results and USDA economic research service map data related to food access. The USDA maps highlighted the areas in Roanoke and Salem with high levels of low-income and low access to a grocery store. The barriers identified were cost, psychosocial factors, nutritional knowledge, time, transportation, cooking skills, kitchen equipment, social support, and children’s preferences. All of these factors, and the information from the maps, were considered in development of the interview guide and in the final recommendations for produce distribution.

A review of the academic literature identified factors that influence produce distribution through pantries and meal programs. There is a common misconception that donated food is free, but donations for pantries and meal programs come with a cost. The organizations have to be able to receive, store, organize, and distribute the donations. Storage can be a problem, particularly if some produce items require cold storage. The timing of delivery is also important. The pantry meal program has to have the capacity to manage the donations. Additionally, there are things that pantries can do to improve access to their fresh produce. One interesting strategy the students found in the literature was neighborhood markets, where pantries set up outdoors, in the style of a farmers’ market. This allows produce to be distributed quickly and in a way where patrons don’t have to come inside or be limited by their choice.

Recommendations developed as a result of the interviews included suggestions of what the garden should produce to meet the needs of pantry and meal program patrons, sorted into high-, medium-, and low-yield categories for different types of produce. The student team also included recommendations for harvest and distribution in the form of a schedule based on partner needs and capacities. All of the data gathered was presented in a report format to The Giving Garden. The garden team has already used the data in three separate grant applications. As of last week, two of those have been awarded, one from Virginia Cooperative Extension and one from a Rotary Club.

For the engagement component, there was a focus on fundraising for construction and marketing as well as for providing education about why the garden was established and who the garden’s partners are. The team utilized in-person donations prior to COVID-19 restrictions coming into place, and they established an online donation platform afterward. They contacted local businesses, as well, utilizing a strategy that provided fundraising incentives. Their fundraising goal was $10,000, to be used to construct the 4,800 square-foot garden space. This included tilling the space, building 20 raised beds and a washing station, purchasing tools and garden materials, and creating safety resources, such as cleaning materials and a poster regarding food safety guidelines.

The team was able to fundraise $5,000 of their goal. As a result of the stay-at-home order, they decided not to do any more active fundraising around mid-March, so they actually only had about a month of active fundraising. The team created a flyer that was distributed and displayed at local businesses. They calculated that a donation of $200 would cover the costs of constructing a garden bed, including materials for planting and maintaining it. Therefore, donors were given the option to donate either $200 or any amount they would like. If they donated $200, a garden bed would be constructed in honor of a loved one. The student team also sent out letters to businesses that outlined the details of The Giving Garden, including the mission and the vision, once again utilizing an incentivized approach. A donation of $200, $500, or$1,000 resulted in the business name being displayed on a garden structure, like a tool shed or entry gate, or having their business acknowledged at a future “planting day” event.

Additional marketing included the use of social media, local media, and word of mouth. They developed a brochure that could be handed out at in-person fundraisers to educate the community about the garden’s partners, the community that they serve, and the use of the funds raised. One of the garden team members had contacts within local news media, and Neesey Payne, a local reporter in the Salem/Roanoke area, did a television news story about The Giving Garden, which increased donations. They also developed a Facebook page, which, aside from email, was their main mode of communication with general stakeholders.

Another deliverable was an implementation plan for the garden, which was created to be a living document that could be changed by the garden team as needed over time. It was developed by gathering lessons from another local giving garden, through exploration of the professional literature, and by review of the assessment data. The implementation plan includes a budget for this year and a yearly budget to be utilized after the initial major infrastructure needs have been met. The budget was reordered a good bit as COVID-19 emerged. For example, the washing station wasn’t a priority initially, but it soon worked its way up to the top of the list.

The student and garden teams decided that improved organizational structure was needed, complete with a leadership team that would be responsible for directing garden activities and decision-making through a group brainstorming and consensus process. They decided that one wouldn’t have to be a gardening expert to be on the leadership team but rather just be willing to commit to learning, growing, and supporting the mission and vision of the garden for at least a year, as well as training a successor. Some of the roles on the leadership team included a team facilitator, a volunteer coordinator, three to five volunteer team leaders, a media manager, a few garden consultants, and a few engagement coordinators. Volunteers would be divided into teams under the team leaders and would rotate duties throughout the summer to ensure that no volunteer was overburdened.

Policies and procedures for garden volunteers were created, as well as a planning and planting timeline based on best practices, learned from the sister garden and compiled from best practices found in the professional literature. In conjunction with the construction and gardening workgroup, the team developed a template for how the garden space should be prepared, with some adjustments in response to COVID-19 distancing guidelines and reduced planting space to be managed with fewer volunteers. The student team also developed a garden space diagram of how they would like to build in the future.

Also created was a planting template that can be used to document where different items are planted each year so that crops can be properly rotated to reduce the spread of plant disease. Additionally, the team addressed a common challenge that occurs when a leader leaves--lost administrative details. To combat this, the team captured as many details as they could in the implementation plan, including an inventory of tools that can be updated regularly by the leadership team facilitator and an email interest list that currently includes over 80 interested volunteers and people in the community.

The final component was establishing volunteer guidelines and providing information about food safety and COVID-19 procedures to make sure everyone stayed safe. This included a handout regarding general food safety in the garden, safe hygiene practices, and procedures for ensuring that they’re harvesting the produce properly and preventing animals from entering the garden. All information is based off of CDC and USDA guidelines and good agricultural practices. The same information is included on a 24 x 36 poster to be displayed at the garden so that people can easily refer to it. Also included was volunteer information, COVID-19 guidelines, and frequently asked questions updated with CDC information. Specific cleaning procedures for gardening tools, food harvesting, and no-contact delivery of produce were outlined to give partners peace of mind that precautions are being taken to prevent the spread of disease.

The team’s program faculty mentor, Dr. Kathy Hosig, stated, “It was wonderful to watch the work that they did and the community-engaged approach that they used.”